“Hey, I nearly forgot,” Matt says handing over a cardboard tube duct-taped on both ends. “This is for you.”

Nikolai looks up from the small table set up in the driveway-stairway combo front of The Eco Hostel. He accepts the gift and returns the greeting before getting back to his beer and conversation with a young woman seated next to him. In twenty, maybe thirty minutes he would open it to discover an origami koi, a ‘thank-you’ for sharing his story.

Matt turns onto the street to catch up with his dinner group. Hugh and Carlijn lead the way to the destination they’d read about online, their respective English and Dutch accents still audible though their words are lost to the city’s evening honks and revving engines. Behind them and last in the group is a fellow American named Suarez. He looks up and lifts his chin to Matt in recognition.

The two of them had met the night before as Matt was picking up the details of Nikolai’s story.

* * *

“Okay,” Matt says in the distracted and slow drawl of someone typing as he talks. “Your friend’s name…was Wolfgang and…he met up with you in Capo Testa…three years before?”

“Four years,” Nikolai corrects. He watches the young man’s thumbs fly over his phone with a smile and relaxed posture. He takes a sip from his brown-glass bottle.

“Okay, got it, got it.”

A backpacker watches them from the other side of the small table just outside their hostel. His half-lidded eyes jump back and forth with each question and answer, though he doesn’t intrude on the rapid-fire interview. His jet black hair is short, though coarse unlike the thinner hair of Southeast Asians. Further separating him from the locals is the equally short, equally dense goatee that covers his chin. His skin is tan, a darker shade that has nothing to do with time in the sun and everything to do with his Mexican-Peruvian heritage. Instead of a regular tank top, he wears one of bleached, rippled cotton. It would be called a ‘wife beater’ back home. His arms are thick, his shoulders broad, and though his face is impassive and blunt there is zero menace in him. He’s just watching. He puffs on a joint he rolled minutes prior, the weed sold to him by a nervous local missing his front two teeth. A couple of seedy grams for 400,000 dong [$20]. A rip-off. But he smokes calmly, just watching. He’s in no hurry.

When the interview is finished, Matt thanks Nikolai and assesses the seated cluster of late-night travelers. He points at the Hispanic backpacker, whom the burgeoning blogger thinks he’d heard someone call Suarez. “Bánh mì time?”

“Sure,” Suarez agrees, climbing out of his seat. “What was that? What were you doing back there?” he asks in a rough Californian accent when they’re crossing the street.

“With Nikolai?” Matt clarifies. “It’s for my writing. I wanted to make sure I got all of his details right.”

Suarez nods. Writing and blogging and stuff. It’s cool, but not really his thing. He prefers things he can see and feel. And midnight fast-food. They step into the florescent lights of the bánh mì chain.. He sniffs the air.

Matt feels the same. “Dude, Samkang,” he knows this store by name by now, “is the best. They do bánh mìs for like fifteen thousand [$0.75] and they’re awesome. I get one for lunch every day.” He reads his companion’s eager-but-lost expression. “They’re like sandwiches with meat and veggies and sometimes pâté–goose liver–and they’ve got this savory type of sauce on the side. Trust me, you’ll love it.

The bánh mì newbie nods. “Dope.” Little did he know, but he’d go back for seconds and thirds of the sandwiches later that night.

But inside, the Samkang employees are still putting together his first sandwich. The usually more-animated Suarez is watching, entranced. This Matt guy he’s with is chatting animatedly to the teenagers behind the counter. He just finished folding a dog or something out of one of these Vietnamese bills and is asking them if they have any crisp or new ones he can trade for. More shocking than the folding he did without missing a beat in the conversation, is the fact that the fast-food visor’ed teens actually open the register and let him lean over the counter to check through the till inside.

“Thanks for the money! And the bánh mì!” Matt hastily adds, holding them both aloft. The shop’s door swings shut slowly behind the pair. He carefully tucks the ‘crisp bills’ into his wallet before ripping a bite from the bánh mì.

“Damn, man!” Suarez breathes, ignoring his own sandwich for the time being. “Where’d you learn to do that?”

Matt chews and swallows. “The origami, you mean? I’ve been doing it forever, since I was four.” Another bite.

This is interesting, this is why Suarez decided to come see Southeast Asia. “What’re you doing tomorrow?”

“During the day, not much, probably another one of these, trying to stay off my feet and let my foot heal. During the evening? You should come with us to dinner, it’s supposed to be good.”

“Yea, definitely, just let me know when and I’m there. Don’t leave without me!”

* * *

“I don’t believe we’ve been properly introduced,” Hugh says across the dinner table.

The next evening, the four of them are sitting around a circular table in Phở 2000, a decently-reviewed noodle shop. All around them, past the identically shaped surfaces, are accolades and newspaper clippings, the most common of which feature Bill Clinton. Apparently the former President likes to eat here when he’s in town.

Suarez looks over and treats the Brit to his signature head nod of recognition. “Hey, my name’s Tony.”

“What?! Tony?” Matt goggles. “I’ve been calling you Suarez this whole time!”

“Yeah, I dunno what that was about, but I just let it happen.”

Everyone but Matt is laughing and he hides behind the menu in mostly mock shame.

“I’m not sure… what I should get…” Carlijn murmurs. She scans the menu of different noodle soups, the common motif being pork/chicken/seafood options for each.

“We were here the other day,” Hugh suggests, “and the pork was incredible.”

Tony eyes his menu, a single laminated page. “Hell yeah! I’m pork-crazy right now.”

“You sure? They do seafood pretty well here in Vietnam.” Matt’s eyes twinkle at Hugh and Carlijn. Their dinner with Thắng had been the night before.

“I know, I know, I was seafood-crazy in the Thai islands,” Tony still sounds excited. “I love seafood, which is weird, ‘cus I do some pretty fucked up fish processing at my job.”

“Fish processing?” the traveling folder asks. “I’ve never heard of it.” He checks to find the other two backpackers equally unfamiliar.

“You know, like taking fish and getting ‘em sorted, red or pink or chum or whatever,” Tony counts off on his fingers. “Separating them, processing them, grading them for stores and shit.” Tony is falling into the comfortable cadence of someone who knows exactly what he’s talking about.

“No way, I’ve never even thought about that kind of stuff.” Matt pulls out his phone, remembering to take notes this time. “I’d love to hear all about it.”

Tony scoffs, eyeing the phone skeptically. “You wanna know about The Slime Line?”

“Hell yeah, man! It’s a totally different life, a different path, and that’s why I’m out here in the first place. It doesn’t all have to be rice paddies and temples.” He brings up his notes app. “Okay, start from the beginning.”

* * *

Tony closes the front door behind him and steps onto the porch in the still-warm California twilight. He pulls a half-charred weed roach from the top of a window sill that he’d hid there earlier because his mom had flipped out at him about it. Whatever. He fingers the the lighter in his pocket, squinting down the street of his San Pedro home.

Palm trees line the streets, streets that are mosaics of graffiti. The sidewalks, the trashcans, anything that could be city property has some spray paint on it. It’s not overkill, not exactly, but there’s definitely enough there to realize that somebody (or somebodies) went on a tagging mission. Down the block there’s a car parked halfway in its driveway, blocking the sidewalk. A group of guys chill around it with a few beers, listening to the pimped out sound system. Their music almost masks the chopping of a helicopter and the wailing of sirens in the distance. Nothing out of the ordinary. Just another day in Cali.

Tony’s twenty-three and he can remember living like this his whole life. He dropped out of high school as soon as he picked up his GED six years or so ago. No reason a man can’t have some letters to him, even if he does make some bad choices. He’d only dropped out to earn more money, to roll with the right crowd. Or wrong one, depending on if you asked his mom. Tattoos of looping calligraphy peek out from beneath his beater, as much a uniform as any he’d ever worn.

He takes a step closer to the road, feeling the bounce in his new kicks. Supposedly, some people know the crooked longshoremen who oversee the shipping containers at the pier. They get the tip-offs to ‘go shopping’ and lift some goods–like new sneakers–right out of the boat. That’s not Tony, he has to get them the hard way: buying them ‘half-price’ by using a phony gift card that was purchased with someone else’s identity. Tony has his own connections. And the other half, the half that he actually paid for, that’s money from pushing dope on any of the countless days and nights holding down the spot and chilling on the block.

Theft, moving drugs, defending territory, it can get fucked at times. He’s buried too many of his brothers. One is too many. He’s twenty-three already, is this his life? Is this going to be his life?

He lights the not-quite-forgotten roach in his hand.

A buzzing in his pocket brings him around and the scrambling to pull it out of his baggy jeans scatters ash onto his new shoes.

He answers, slightly agitated. “Yo, what is it?”

It’s his cousin Ruben. He talks, Tony listens. Tony’s not usually the listener unless is someone like Ruben doing the talking. Ruben will talk and talk and you just gotta let him get it all out or he’ll be too word-constipated to have a real conversation. He’s one of those people who needs other people like a fish needs water. Without someone else he’s barely sure enough of himself to take a shit on his own.

When he’s finished with his verbal diarrhea, Tony puts his cousin’s blabbing more succinctly. “You want me, to come with you, to Alaska?”

Yes, Ruben can’t do it just on his own. It’s working in a fish processing plant, just easy manual labor type of shit. See, it’s his step-brother’s grandma’s brother who can get him a job and they don’t care what kind of background or education you’ve got, as long as you do the work. And the money’s good and you only do a couple of months a year.

Tony’s says nothing.

The only sound Ruben hears is a puffing on the nearly-gone joint. “So you gonna do it or what, man? You gotta do this with me, I can’t go up there alone.”

* * *

Three years later Tony hears the boat call and his eyes flutter open. He straightens his rubber coat and steps up with care. You have to be careful, the blind spots in the camera system aren’t very big. Big enough for a quick nap between boat calls on a thirty-fucking-hour shift, but not much more.

Tony knows where all the best spots are by now, better than the supervisors. He’s a Dockworker, whose main job is to unload the fishing boats coming in with their hauls. All summer, from May to August. It’s not quite as cushy as a longshoreman’s gig in Cali, but it’s as high as you can get on The Slime Line without being a supervisor. And he’ll probably move on to that next season. Ah, it’s kind of a dirty work environment, but who’s he to complain? The money’s clean.

He’s flagged down by one of the other Dockworkers and he hops over to the boat that’s just come in. They lift the heavy suction tube and fit the steel ring of the tube into the associated port on the ship. Twist, lock, and flip the switch. Wet slaps echo as the salmon in the boat’s hold are shunted down into the tanks in the processing facility. In his mind, Tony can see the dead, chilled fish racing away and follows them as they go.

Tony should know what happens to them, he’s worked his way through the entirety of The Line. First the salmon go into the hopper where it’s the newbies’ job to make sure they’re coming out onto the conveyer belt at an even speed. Don’t fuck it up or you fuck with everyone’s jobs. Then the Sorters group fish by type and size. Red, silver, pink, pink, pink, chum, chum, hump, king, red, silver, silver, silver, chum, king, hump… Assess, sort. Assess, sort. Assess, sort… Hours on hours of grabbing and arranging fish. It gets to the point where you don’t even see the fins or blank eyes staring at the ceiling. You look at the scales and that’s enough to tell what kind it is.

If you can do that, you ‘graduate’ to getting your hands dirty. Now it’s your job to take fish of one type and slam them down onto the pins sized and designed just for them, right through the gills. Get it into the gills and get it stuck in hard. Fuck it up and when the machine a few yards down from you comes down with its blades to chop off the heads, everyone will know you done fucked up. Blood that’s normally everywhere is now everywhere. So slam it down hard and the guy beside you who’s lining up the newly-headless fish won’t hate you. All he’ll be thinking is the same thing every guy who lines up the fish thinks: Heads up, bellies out. Heads up, bellies out. Heads up, bellies out…

If Tony had thought lining up fish in grooves was monotonous, the next job set him right: The Belly Slitter. It’s your responsibility to take the knife they sharpen god-knows-how-often and cut the headless, bleeding salmon top to bottom. The best can do it in less than a second or two, which is the way to go because as soon as you make that cut, the organs start popping out like they’re spring-loaded. You don’t eat before your shift as a Belly Slitter.

And you won’t eat after your shift as a Gut Puller. After the fish is cut open you’ll find the lucky gentlemen who’ve won the opportunity to reach into the splayed-open animal, find the point at the top where all the organs meet, and rip the whole bunch out. Sometimes they don’t come out all at once and you have to fish around inside for them. You learn how to find that point quickly. Everything you pull gets dumped into a trough of running water to carry it all away for sorting.

That’s right, somewhere in another room, people are poring over the river of organs for the roe sacs (God help the Slitter who accidentally rips those sacs open). They’re pulling the sacs out and setting them aside to be shipped elsewhere. And there are Japanese men standing over the sorters, making sure they do it right. Always Japanese supervisors. Unless it’s pollock that you’re processing. Pollock season comes a few months earlier than salmon–a great way to stretch your earning season. All the pollock’s organs get separated out: livers, hearts, whatever-the-fuck-else-is-inside, all to make those imitation crab sticks.

Back to The Slime Line. By this point the conveyer belt is covered with scales. Scales crunch in the wet gears and crackle under booted feet. They’re supposed to be cleared away routinely, but almost three-quarters of the employees are tweakers or addicts, barely functional enough to punch in everyday, let alone do their jobs properly.

One time some moron sprayed his hose right at the ground in front of Tony, scattering scales mostly off into the drains. Mostly. One shot right into Tony’s eye. Shouldn’t he have been wearing goggles? Yeah, sure, if he didn’t mind staring at nothing but fish guts all day. That is, fish guts right on his goggles instead of down on the belt. Either way, he ended up running and cursing up to the second floor where they kept the only working eyewash (despite regulations demanding they have one on every floor). Tony had raced past the floor manager, Dom, who’d only shouted after him to remind him how replaceable he was. Like hell he was; Tony’s one of the few guys who knows what the hell he’s doing.

Like, after the guts are pulled, there’s the Second Slitter. His role’s to cut into the spine and whatever’s left over for the next guy to scrape out with a spoon and dump into that water trough. Plenty of guys’ hands are too shaky from a night of whatever shit they’re into and they’ll catch on some bones and slice open their hands. When that happens there’s almost as much blood as from the salmon’s spine or whatever it is that poor son of a bitch has to dig out with his metal spoon. Just scrape and ignore the smell. Scrape and ignore. If they made better vacuums, the stage that comes after the spoons to pick out any stray bits, they wouldn’t even need to scrape shit out at all. It must be cheaper just to give some bastard a spoon.

Once the fish has been properly mutilated, each one is graded on a three-point scale between ‘excellent’ and ‘dog food’. Arranged by size and grade, they’re flash frozen on thick sheets. The frozen carcasses are pulled out in thick panes of ice, like Han Solo in carbonite, and hurled to the ground to release them. Technically you’re not supposed to throw them on the ground, but Tony’s still listening for a better way to get them de-iced.

Lastly, the frigid, rock-solid fish are tossed into a pool of salty brine. They flip and rock in the current until they’re pulled out on the other side, shiny and coated in a clear, clean layer of frozen salt water. Glazing, this final stage is called and it makes the fish look beautiful. The pink-orange flesh almost looks appetizing, scrubbed of the brutality of the last sixteen hours of its existence.

Yeah, it takes a full sixteen hours for the salmon to move from dock to packing, and Tony’s seen it all. At the red light flashing on the hull, he knows his boat’s empty of its cargo. He twists off the hose and hauls it back to its holster. He flexes his right hand and hopes the bandage isn’t coming loose.

Last week he was helping out on the forklifts and noticed his forks were out of alignment. He tried to set them right, but in gripping the industrial-grade metal, he slipped. It sliced his hand open right down the palm. Blood and profanities poured out of him.

When he was in the doc’s office that evening, Dom was with him. Mandated by the company he said. He also said that Tony’d have to be back on the docks in forty-eight hours, that workmen’s comp didn’t apply in this situation. The doc had been shocked to hear it, but Tony didn’t object. He couldn’t. Workmen’s comp would require a drug test and he might as well be pissing green for all he smoked in his off hours.

So Tony just shakes his head and watches the cameras carefully. He calmly makes his way back to the pallet of sacks of salt that he uses as a makeshift bed. He smiles despite the slow throbbing in his hand, he’ll be free in a few weeks, at least for a time. He sinks into sleep immediately and dreams of his vacation to Thailand and Vietnam.

* * *

“And after the freezing comes the glazing, and then that’s it, right?” Matt double-checks.

Tony’s stories and Matt’s prodding for more details have taken the better part of the evening. Now they’re sitting at the outdoor tables at Crazy Buffalo, a bar on the corner down from the hostel.

“You got it.” Tony swigs his beer. “I can’t believe you’re writing this all down. You really think this is interesting?”

Matt’s eyes dance. “Tony, this is precisely what I want to write about.”

“If you say so. It’s not like I’m that barefooted guy you were telling me about. That guy sounds–” Tony’s cut off by Hugh, power walking back to their table.

“Guys! You gotta get to the gents and check out the urinals.” The Brit’s grinning like a schoolboy. “Right where you piss, in the trough, they have a sheet of clear plastic and underneath are a pair of TVs set to FOX News. You get to piss on FOX!” He spreads his arms in glory.

Neither of the Americans are listening anymore, thoughts of writing and salmon gone from their minds as they clamber to get to the men’s room. This is what traveling’s all about.

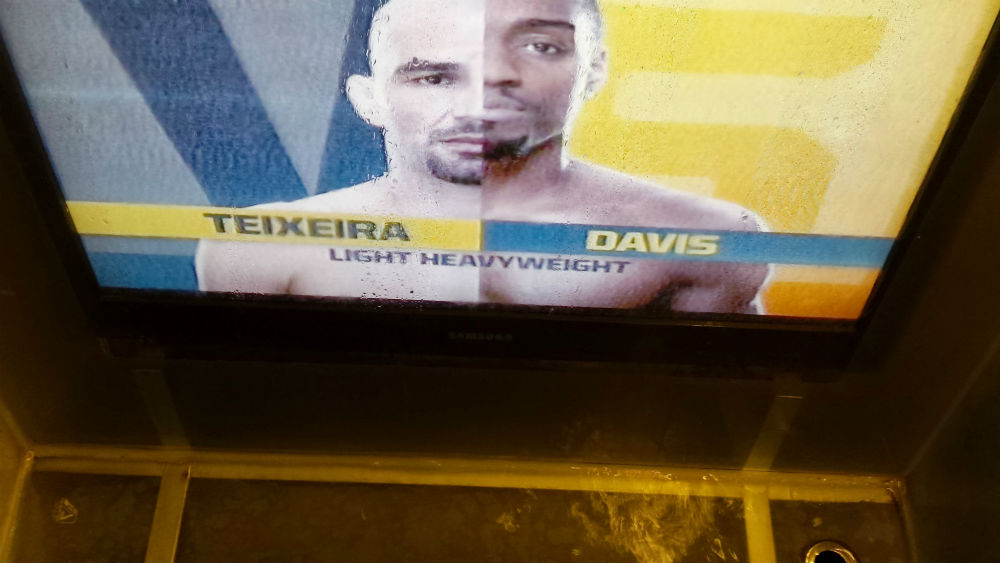

For the curious, this is what it looks like to piss on FOX News at a bar in Vietnam. Couldn’t get a shot with the talking heads, but they were there.

One of the kind Samkang employees making our sandwiches

A tank on display in downtown HCMC, a replica of the one used to storm the President’s quarters in the final push of the Vietnamese Civil War